Over the next number of weeks we will be talking about one of the most important topics in Irish history, the Easter Rising. Here is a quick introduction that has been written by en expert in Irish history, Adam Ladd.

Every country has a date in history that it sees as their moment of conception. These dates and the events they mark can change vastly on a country by country basis. If you go to America that date is 1776, the Declaration of Independence and the beginning of a War of Independence. In Canada that date is 1867, the creation of the Dominion of Canada. In Australia that date is Anzac Day and 1915, stemming from the coming of age of Australia’s population on the cliffs of that ill-fought Gallipoli campaign. What these events have in common, albeit slightly different in nature, is that they all end in success; American victory in the Revolutionary War, Canadian statehood and in the case of Australia an Allied victory in the Great War. In Ireland however that date is the Easter Rising of 1916. This event ends in a comprehensive military defeat of the Republican forces, mass internment and the execution of the Rebel leaders. It did not win Ireland a republic in 1916, or even in the immediate aftermath. The culmination of this would lead to a partitioned Ireland, one state remaining within the United Kingdom and the other a dominion of the British Commonwealth. It would be 1949 before an Irish Republic would officially come into being. Yet, in spite of all this, the Rebellion of 1916 and the short lived Irish Republic proclaimed on Easter Monday continued to intrigue, fascinate and inspire the Irish people to this very day. How did five days of fighting come to define a nation? This article seeks to begin to investigate this question.

Context

Ireland’s relationship with Britain is one which stems back many centuries, in fact few nations on earth can point to such an unbroken continuity of conflict than these islands in the North Atlantic. One can trace this back to the year 1169 and the Anglo-Norman ‘invasion’ of Ireland. The so-called invasion was in reality an invitation on behalf of the King of Leinster King Dermot MacMurrough. MacMurrough’s name has many alternative spellings but for many Irish people ‘traitor’ is the most common, Dermot often portrayed as the ultimate villain in vast pantheon of Irish History (a mean-feat considering his competition in the likes of Henry the 8th and Charles Trevelyan). Over the next seven and eight centuries the Lordship of Ireland and later Kingdom of Ireland would pass into Anglo-Norman, English and British hands. The relationship between the countries was typical of what one would expect of a subjected nation and their colonial oppressor. The British state’s relationship with India was a comparable situation. However, unlike India, there was something Ireland never had, a vast supply of natural resources or natural minerals. The British occupation of Ireland in many cases was simply a colonial necessity given the geographic proximity of the two islands. Ireland was too close to ever be allowed to leave the empire but in reality was too far away to ever fully be incorporated harmoniously into the British state.

Resistance against British Rule

Attempts to overthrow British rule in Ireland are not few in number in the last 800 years, but for the vast majority of that period it was often Gaelic Chieftains who sought personal power over their Anglo-Norman rivals. To paint these leaders as Irish nationalists is a bit of a stretch. Brian Boru, famously labelled ‘the last High King of Ireland’, was in reality a war monger akin to any other at the time. Later centuries would give rise to the famous O’Neill clan, most prominent was the renowned Red Hugh O’Neill. However the classification of the Nine Year War and later events like the Kilkenny Confederacy as Nationalist revolts is a tad disingenuous. When this does become clearer is the late 18th century when for the first time the idea of Republicanism bursts to the fore in revolutionary France and America. The concept that individuals were to be equal citizens, regardless of class, and were no longer subjects of the crown was attracting converts all across the world. This too would find favour in Ireland with revolutionary works such as Thomas Pain’s ‘Right of Man’ selling thousands of copies. Republicanism however did not merely unite social classes in Ireland but it also united creeds. The foundation of the United Irishmen in 1791 is a testament to this fact. Formed by Presbyterian intellects from Belfast, initially the group sought parliamentary reform in Ireland but with reform evidently not forthcoming the reformers became the revolutionaries. By 1798 the group had launched Ireland’s true firsts national rebellion under the flag that read ‘Erin go Bragh’, Ireland forever. Although ultimately ended in defeat following five months of fight the wide scale fighting it marked a new phase in Anglo-Ireland relations. Almost as if laying down the gauntlet the United Irishmen rebellion would inspire Republican revolts in 1803, 1848, 1867 and 1916. Similarly it would also begin a pattern of Irish Republicanism looking abroad for foreign aid be that from France, America or later, even Germany.

Constitutionalists

As well as sparking a wave of militant republican uprisings the Enlightenment would also lead to an increase in parliamentary participation across the world. In Ireland however that parliamentary action was to take place in London as opposed to Dublin from 1801. The Act of Union had formally merged the Kingdom of Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland, a move attributed to the United Irishmen rebellion just two years prior. This act would have disastrous consequences for Ireland, something particularly evident during the later Irish Famine period of the mid-19th century when an Irish government would have surely more ably dealt with crisis in Ireland rather than a physically, and emotionally detached government in London. In Ireland the nationalist movement was thus divided into two camps, those committed to the violent overthrow of British rule and those who sought modest constitutional reforms in Westminster. The latter would later become known as the constitutional nationalists. That movement had two significant leaders, Daniel O’Connell and Charles Stewart Parnell. The former would secure Catholic Emancipation, the abolition of anti-Catholic laws in Ireland but died without achieving his ultimate goal of repealing the Act of Union. Charles Stewart Parnell would come to prominence in the 1870s as an elected member of parliament. Prior to that decade elected Irish members tended to be Liberals or Conservatives like their British counterparts. Parnell took a loose Irish cohort that sat together and formed the Irish Parliamentary Party, or simply the Irish Party. This grouping for the first time gave Ireland a unified political voice, a voice that often held the balance of power in parliament. The movement had two main objectives; land reform and home rule. Land reform was achieved by the 1880s following a series of land acts as part of an alliance with the British liberals dubbed the ‘Union of Hearts’. Their attention therefore turned to Home Rule.

Home Rule

Ever since the abolition of an Irish parliament in 1800 there was always a movement to restore it and grant what was called Home Rule. The old parliament was far from perfect, the members of the parliament were drawn from the Protestant ascendency with Catholics excluded from the democratic process. Even at that the powers the Irish parliament had were quite limited but it was an Irish parliament, the symbolism was extremely attractive even if the substance was lacking. For the Irish Parliamentary Party this was their ultimate goal and they presented it as such. They never openly advocated for separation of the respective states by contrast they argued that such an institution would heal the democratic deficit Ireland had suffered and would actually improve relations, ultimately securing Ireland’s permanent position within the union. It was through the aforementioned alliances with the British Liberals that produced the First Home Rule Bill in 1886. Although the Bill was presented to the house by the Prime Minster William Gladstone he failed to secure the full backing of his party and the bill narrowly was rejected by the House of Commons. After regaining power in 1892 Gladstone reintroduced a 2nd Home Rule Bill the following year. This time the bill did receive backing from the House of Commons but Conservative dominated Horse of Lords heavily rejected the Bill. The veto power of the Lords meant that such a bill was unlikely ever to pass but the Parliament Act of 1911 amended that veto power to merely power to delay a bill for two years, thus seemingly paving the way for Home Rule for Ireland. The 3rd Home Rule Bill became the Government of Ireland Act 1914 and was written into law. Nationalist Ireland in unison celebrated in exaltation for in two years it would, once again, have a parliament.

The militants strike

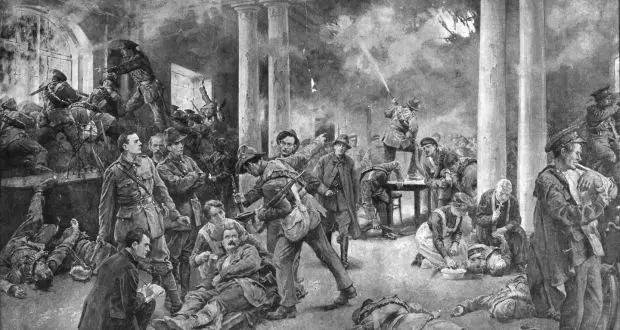

All the while the smaller militant movements in Ireland sat by and watched from the side-lines. The movement numerically and physical was probably at its strongest by 1914. The militants had infiltrated the ‘Irish Volunteers’, a home guard of sorts, nominally run by the Irish Parliamentary Party. The volunteer army was formed in response to the Ulster Volunteers in the North of the country. The Ulster Volunteers were formed to pressure the UK government to reject Home Rule while the Irish Volunteers were formed for the opposite reason. It seemed as Home Rule had worked its way through the parliamentary process that civil war between the two militias was inevitable. However such a conflicted was superseded by events in Europe and the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The killing thus ignited Europe into ‘the Great War’. In relation to Home Rule the British government announced Ireland must wait and that the act, although passed into law, would have to wait until the end of the conflict for implementation. The parliamentary party thus urged the Irish Volunteers to join the British army to show loyalty and ensure the post-war enactment of the law. The traditional militants in Ireland rejected this notion that Irishmen should die in Europe fighting for ‘King and Country’. The reconstituted Irish Volunteers controlled by the militants numbered about 15,000 nationwide, a small proportion of the pre-split membership of 200,000. Believing that the implementation of Home Rule was unlikely this rump now openly preached armed rebellion, stating that ‘England’s difficulty is Ireland opportunity.’ Its leaders began planning a nationwide rebellion, by Christmas 1915 the date was set for the following Easter and on Easter Monday 1916 the long awaited rebellion began.

The rest as they say is history.

This article was written by Adam Ladd. One of the highest rated tour guides in Ireland, with a masters degree in Irish history and experience in Kilmainham Gaol (where the leaders of the rising were executed), Adam was also involved with the celebrations around the 100 year anniversary of the rising in 2016.