This article was written by Adam Ladd. One of the highest rated tour guides in Ireland, with a masters degree in Irish history and experience in Kilmainham Gaol (where the leaders of the rising were executed), Adam was also involved with the celebrations around the 100 year anniversary of the rising in 2016.

In our ongoing effort to help people understand Ireland a little better, I have gotten back in touch with Adam to help explain a little more about Irish politics and the interesting background to some of the stuff that goes on in Ireland even today!

Introduction

To understand the Irish politics, one cannot divorce it from the context of Anglo-Irish relations. As discussed in a previous article (HERE) Ireland for most of its modern history has been under rule from Westminster, save a brief period of self-autonomy in the 18th century. Thus, in this context the Irish political system under British rule can be divided into two categories; those who sought independence, the Nationalists, and those who opposed independence, the Unionists. As well as being politically divided the two ideologies were also geographically divided too. Unionist found its stronghold in North-East Ulster (this area largely encompasses the Northern Irish state today) and pockets of urban affluent Dublin. Nationalism by contrast was a much more geographically wide phenomenon, one subscribed to by most of the island’s population. In this context therefore, the intrinsic political platform put forward by the respective political parties (The Irish Parliamentary Party and the Irish Unionist Party) mattered little. The main raison d’etre for voting for these parties was down to their position on the national question, something which has survived today in the Northern Irish political system. It was however the seismic political upheaval at the beginning of the 20th century that would disrupt this status quo.

Historical Context

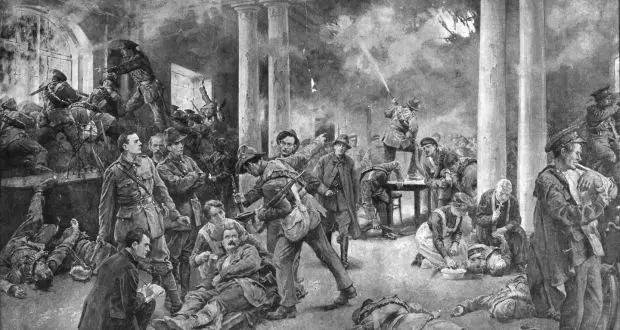

The 1916 Easter Rebellion and the executions that followed would spark a political revolution on the island, one that Irish poet W.B. Yeats would term ‘a terrible beauty’. The subsequent War of Independence (1919-21) would result in the Anglo-Irish treaty signed between Ireland and Britain, a long and complex document. For the purposes of this article the main points of note were the partition of Ireland into two states; the Irish Free State in the South and Northern Ireland in the North. Despite its name, the Free State had many attachments to their former colonial master, the one that irked the most was the requirement for members of its parliament to swear an oath of allegiance to the British Monarch of the day. These clauses would lead to an eruption of Civil War in the new Free State between those who accepted the compromises, The Pro-Treaty side, and those who rejected it, the Anti-Treaty side. This bloody and bitter conflict would rage for 11 months over the course of 1922-23 and cost the lives of more civilians and combatants than the proceeding Easter Rising and War of Independence combined. Ultimately the pro-Treaty side would emerge victorious from the conflict, but the division of this conflict is still evident in modern day Irish politics.

With the military division now established the political one would soon follow. Two major parties would emerge from the ashes of the Civil War; pro-treaty Cumann na nGaedheal (meaning the Group of Gaels) and anti-treaty Sinn Féin (We Ourselves). Cumann na nGaedheal would emerge as the largest party in the first post-conflict election winning 63 seats of a total of 153, their rivals winning 44 seats while smaller parties would gain the rest. Although the largest party Cumann na nGaedheal did not have an outright majority and under most normal proportional representation systems would need to form a coalition government with a smaller party such as the Labour Party. This however was not the case in the Irish Free State of 1923 due to the abstentionist stance of Sinn Féin. The party had since its foundation held this policy which amounted to refusing to take their seats in the British parliament in Westminster in London. The two main objections the party had was that taking their seats would involve taking an oath of loyalty to the British Monarch and thus in the process they would be legitimising British rule. The Sinn Féin party thus held the same policy as regards the new Free State parliament (and indeed the new Northern Irish one too). As such Cumann na nGaedhael, under the leadership of 1916 Rising veteran W. T. Cosgrave, assumed power in the new state while Sinn Féin, under another 1916 veteran Eamon De Valera, sat on the side-lines.

The Emergence of the Modern System

Over the course of the first term of parliament post-Civil War, the Cumann na nGaedheal party ruled effectively as the majority party in parliament due to the absence of Sinn Féin. It soon became evident to Eamon De Valera that abstentionism was only a viable option if the abstentionist party had the support of most of the people, as Sinn Féin had following the UK general election of 1918. Thus, he would propose a motion at the next Sinn Féin annual conference to drop the abstentionist policy. Following a narrow defeat of the motion, De Valera and a large rump of the party would resign in favour of forming a new political party, Fianna Fáil (The Soldiers of Destiny). This party would be led by talented able figures, such as Sean Lemass and Frank Aiken, who commanded a large body of respect within the Republican movement. Little did they know at the time, but they had just founded what would go onto become one of the most successful political parties in the history of European democracy.

The First election the party would contest would be the 1927 General Election and saw them win a stunning vote finishing only 3 seats short of Cumann na nGaedheal. The party for the first time would have to swear an oath of loyalty, one which De Valera would describe as ‘an empty formula’. This clearly illustrates the pragmatic nature of the new political entity who still maintained a military alliance with the IRA (albeit largely inactive). It was such an alliance that prompted Sean Lemass to comment in 1928 that they were ‘a slightly constitutional party’. This alliance was important however as it gave the party not only a legitimacy amongst republicans but essentially an army of perhaps 20,000 who could, and would, be mobilised for electoral purposes. This would bear fruition at the next general election of 1932, which Fianna Fáil would fight on a mandate of abolishing the oath of allegiance and adopting a protectionist economic model in sharp contrast with their rival’s free trade mantra. De Valera’s party would be just shy of an overall majority and would thus form a minority republican government for the first time in the new Free State. Unsure if their rivals would accept this result many of Fianna Fáil’s members would arrive into the first sitting of parliament with loaded pistols in reserve. Thankfully the electoral result was not resisted in any military fashion and the peaceful change of government marked a major moment in the democratic transition of the new fledgling state at a time when many of its European counterparts began to fall to either communism or fascism.

Building Sovereignty

True to his word De Valera began to pursue an autarky policy in Ireland, refusing to pay land annuity payments to Britain as agreed under the treaty of 1921. This refusal sparked what is called the Economic War between Ireland and Britain with tit-for-tat tariffs being placed on imports. A common rallying cry in Ireland that was often heard was ‘burn everything English but their coal!’ This dispute combined with the effects of the Great Depression led to very harsh economic times in what was essentially an agricultural state. Despite this fact, De Valera and Fianna Fáil’s popularity increased during the period, with the party winning an overall majority in a snap election called in 1933. This essentially gave De Valera free reign on governance in Ireland and would lead to perhaps his longest lasting legacy in Ireland, the 1937 Constitution.

The process that produced the 1937 constitution was a long process that involved consultation with various individuals and interest groups. The document (following a national plebiscite) would replace the existing Free State constitution that was seen by many in the Republican movement as a British constitution. However, its new Irish replacement was not without its point of contention. When talking about the role of women the document recognises that through ‘her life within the home, woman gives to the State a support without which the common good cannot be achieved’. Likewise, the following article also states, ‘The State shall, therefore, endeavour to ensure that mothers shall not be obliged by economic necessity to engage in labour to the neglect of their duties in the home.’ This rhetoric sparked fury within the feminist movement at the time as this view of women’s role in society contrasted sharply with the 1916 proclamation which promised to ‘cherish all of the children of the nation equally’. The articles surrounding religion were equally controversial with the document recognising ‘the special position’ of the Catholic Church. The following article also recognised the role of non-Catholic religions such as Anglicanism and Judaism. From the atheistic the recognition of the special position of any religion was unacceptable but from the Catholic hierarchy’s position the refusal to mark Catholicism as the official state religion was equally unacceptable (Spain, Italy, Poland and Portugal would all recognise Catholicism as their official state religion in this decade).

The document itself would rename the state, it was no longer the Irish Free State but rather ‘the name of the State is Éire, or, in the English language, Ireland’. Likewise, De Valera’s republicanism would shine through when denoting the state’s borders as being ‘the whole island of Ireland, its islands and the territorial seas’, i.e. including Northern Ireland. The Irish language was to be the official language of the state under the document with English given a secondary status. It would also establish a bicameral system like the Westminster model, with the lower house being Dáil Éireann (Irish parliament) and the upper house being the Seanad (senate). The lower house would be led by the Taoiseach (chieftain, i.e. Prime Minister) who would have the legislative power in the country while it also provided for the creation of the office of Uachtarán na hÉireann (President of Ireland) which would serve in very much a ceremonial capacity akin to a monarch. Most importantly perhaps was the article concerning editing the document, this provided for referenda of the people as a means to edit, delete or add articles. At the time of writing 36 amendments have been put to the people of which 30 have been accepted, the latest being the decision to remove the crime of blasphemy from the constitution in October 2018.

The adoption of this new document would be another huge step in building sovereignty for the new fledgling state, another huge step would come the following year. By 1938 the Irish and British states had been involved in the aforementioned economic trade war for 6 years. One of the central grievances from the Irish perspective (aside from the land annuities) was the retention by the British state of several strategic ports as agreed under the 1921 treaty. These three ports, Cobh, Bereheven and Lough Swilly were vital for foreign policy defence from the British viewpoint, from the Irish standpoint they were a key denial of sovereignty. A subsequent agreement that ended the trade dispute also included the handing over of these bases back to the Irish state. This was a key moment in the process to establish an independent foreign policy from her former colonial oppressor. Thus, when Europe once again would erupt into war in 1939, Ireland would remain neutral while Britain was an active combatant. Although neutral during the period Ireland did undergo serious shortages which resulted in the introduction of rationing during a period known as ‘The Emergency’ in Irish history. The neutrality practiced can also be described as nominal at best, the state unofficially backing the allies. This was done in very covert manners such as allied troops who ended up in the state being allowed to ‘escape’ to Northern Ireland. De Valera also allowed the Americans use the Donegal corridor which involved them flying over Irish airspace to get to Northern Ireland. Similarly, when Belfast was subject to the Blitz by the Luftwaffe the Dublin fire brigade were sent to help alleviate the damage. Such examples are just but a subsection of Irish help given to the allied cause, but it did not help Ireland from being the subject of attack in Churchill’s victory speech who criticised the state for failing to become an active belligerent. The response to this was probably De Valera’s finest hour, although the speech is worth reading in full, I will only quote one small section;

Mr. Churchill is proud of Britain’s stand alone, after France had fallen and before America entered the War. Could he not find in his heart the generosity to acknowledge that there is a small nation that stood alone not for one year or two, but for several hundred years against aggression; that endured spoliations, famines, massacres in endless succession; that was clubbed many times into insensibility, but that each time on returning consciousness took up the fight anew; a small nation that could never be got to accept defeat and has never surrendered her soul?

The Modern State

Following the Second World War it could be the state was a fully sovereign one, almost unrecognisable to the dominion established under the 1921 Treaty. The final act of political separation would be the leaving of the British Commonwealth and the declaration of a Republic. This move was something which had been long muted by De Valera who had diluted the role of the British state during his tenure. For example, under the terms of the 1921 agreement Ireland would have a Governor-General, the crowns representative in Ireland that would, as time progressed, become a ceremonial position. De Valera’s adoption of new laws, allowing him to appoint individuals to this position led to laughable situations whereby he would appoint Irish Republicans who although officially were the Governor-General refused to attend to any of their official functions. The relationship with the Commonwealth was therefore a precarious one at best and with the post-war realignment of Europe Ireland was to take advantage of Britain being preoccupied elsewhere with events such as the Berlin Blockade. It was not De Valera however that would be the one proclaiming the Republic, it was his Civil War rivals in Cumann na nGaedhael, now renamed Fine Gael.

The 1948 election once again saw Fianna Fáil emerge as the largest party albeit just shy of a parliamentary majority. Despite this they were consigned to the opposition benches as a large inter-party government took charge. Although in the eyes of the Irish political system Ireland was effectively a republic, in a legal sense this was not the case and thus separation from the British Commonwealth became the final goal in attaining full sovereignty in the new state. The announcement of this move however would not take place in Dublin or indeed London but rather it would take place in Canada. While attending a meeting of heads of state the Irish Taoiseach took offence to the absence of a toast to Ireland. Upon enquiring why, he was duly informed that the Prime Minister of Canada had already toasted the King, and this encompassed Ireland as it was a member of the Commonwealth. The Taoiseach John A. Costello reportedly ran out of the room and rang up his Minister for Foreign Affairs in Dublin. He informed the Minister that he was going to declare Ireland a Republic and as such he should prepare the relevant legislation. True to his word Costello would re-enter the meeting of heads of state and seemingly on a whim fuelled by an ego hit he would declare Ireland a Republic. Thus, the final political separation would be complete by Easter Monday 1949 as the legal text would formally become law.

Impact

From 1949 onwards, the Irish state became a fully sovereign political entity with little or no political ties to the United Kingdom. Economically this however was not the case as the Irish state was vastly reliant not just on imports from the UK market but also the ability to export its excess agricultural output to it. Even up until the 1970s the Irish currency would be pegged to its next-door neighbour’s. The vital move of economic independence came in 1973 with Ireland (and indeed Britain’s) joining of the European Economic Community, now the European Union. This granted Ireland access not only to new trading markets but also access to new grant system. As Irish trade expanded across the free trade zone its farmers benefited from access to the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) grants while the states national infrastructure was built up with the help of the European Development Scheme. Domestic politics remained relatively stable with Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael exchanging positions each election as the government. The backdrop of the eruption of violence in Northern Ireland was one which provided brief reactions from the southern state but nothing major came of this until the ending of the conflict with the signing of the Good Friday Agreement of 1998. This treaty is one which the Irish state is a co-guarantor of and one which established several North-South bodies (e.g. Tourism Ireland, Waterways Ireland) and several East-West bodies (e.g. British-Irish intergovernmental council). As such it has propelled the role of the Irish state to the forefront of European politics in recent times particularly during the Brexit debate. The abandonment of violence and abstentionism in Ireland by Sinn Féin has also seen its re-emergence under a new post-conflict leadership. This combined with the economic collapse of 2008 has led to a new fractured political system. Gone are the days of single party governance and the passing of the torch between the two Civil War rivals, instead there has been an ever-clearer division of the parliament along classic left-right politics which was not in the state due to the Civil War. Likewise, the parliament has become more politically fractured with more parties than ever having political representation, a phenomenon perfectly normal for a system which uses the proportional representation voting system. In light of this ever changing political system and the ongoing Brexit debate this article may be shortly in need of editing but in the meantime hopefully it serves as a starting point in your comprehension of the Irish political system, one which cannot be divorced from history.